Dr. Atomic

DOCTOR ATOMIC (2008 The Metropolitan Opera, New York + 2009 English National Opera)

I had never directed an opera for the stage. In fact I had never directed anything for the stage. I had made an appearance in an experimental play called Liberty and Other Intoxications directed by Mario Trejo who had worked with the legendary Living Theatre when I was eighteen in Buenos Aires. We did well at the Di Tella Centre which showed challenging art and performance under the Onganía dictatorship, unpleasant but not as gruesomely murderous as Galtieri eight years later. The Di Tella was closed down then and tens of thousands of people were tortured and killed. But in 1968 when we went on tour to Mar Del Plata we were all arrested and I shoved in jail for a few hours with prostitutes. It was a shock to a middle class girl from private school. My life became chaotic after that, running off with the most unsuitable man I could find and having a baby with him in Spain. Well I had a baby by myself.

I have never really liked traditional theatre, being trapped in an expensive, uncomfortable seat watching people pretending to be in their front rooms, reading the newspaper and shouting at each other is my idea of hell. But opera is different. To be fair promenade theatre is different too, there is often something thrilling about that. It’s just that naturalism in theatre doesn’t work for me, film does it much better.

But there is nothing naturalistic about opera, you just have to surrender to it. When it works it is overwhelming, appealing to all the senses and shaking you to the core. People find it strange that I love rap and grime as much as opera. They are extreme forms, thumping you in the chest and taking no prisoners and I like that – it’s the mush in the middle that I struggle with. Both are also narrative and I love stories.

John Adams had written a new opera, Doctor Atomic about the Manhattan Project. It had a libretto by Peter Sellars and was about the making of the first two atomic bombs and I was asked to direct it at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. (See programme notes.)

I had filmed The Death of Klinghoffer so I knew that the music dictates everything. You can’t change the pace in the edit and you must always make the action fit the music. But directing for the stage was a differently delirious game. It's obvious really, Doctor Atomic had scenes in the desert, in a laboratory and in a bedroom, sometimes simultaneously, and they all had to happen in a box, behind the proscenium arch. With a film you film on location and that's that. Plus singers need to face the audience to avoid their voices floating off upstage or into the wings - singer kiss and then turn to sing I love you to the stalls. In some ways having these constraints is liberating, you have to invent your way out of it, specially with everyone singing the whole time and an orchestra in the pit.

You start off working with the designer you choose with a scale model of the theatre that looks like a dolls house with tiny little figures that you can move around tiny little furniture. You also work with a casting director and if you are lucky you have some say over the singers. Each house has its own chorus who sing and act in all productions but the individual singers are all freelance like actors.

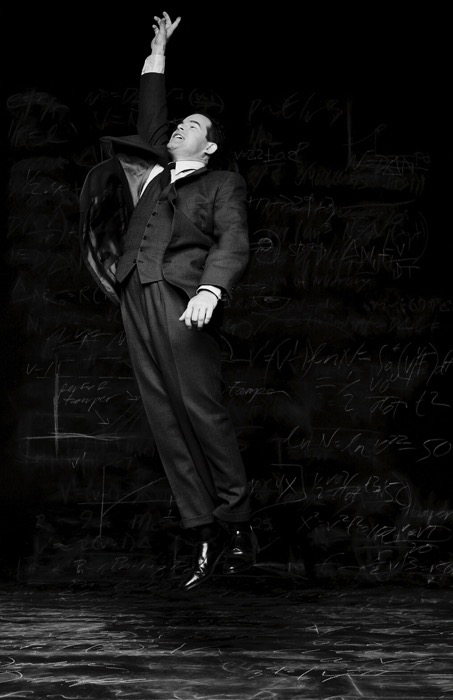

You begin rehearsals in a big room, with the principal singers, some of the set if you’re lucky, with a pianist, a conductor and a number of stage managers, assistants, a props person, sometimes a prompter and a language coach. On the days you have the chorus you can have almost a hundred people in a room. It’s like being run over by a truck while directing traffic. But fun too and the best thing about it is that you have wonderful singers singing for you. A lot of the time they are marking rather than singing out but it is still beautiful. In Doctor Atomic rehearsals I wept every time Gerry Findlay sang Batter My Heart at the end of the first act.

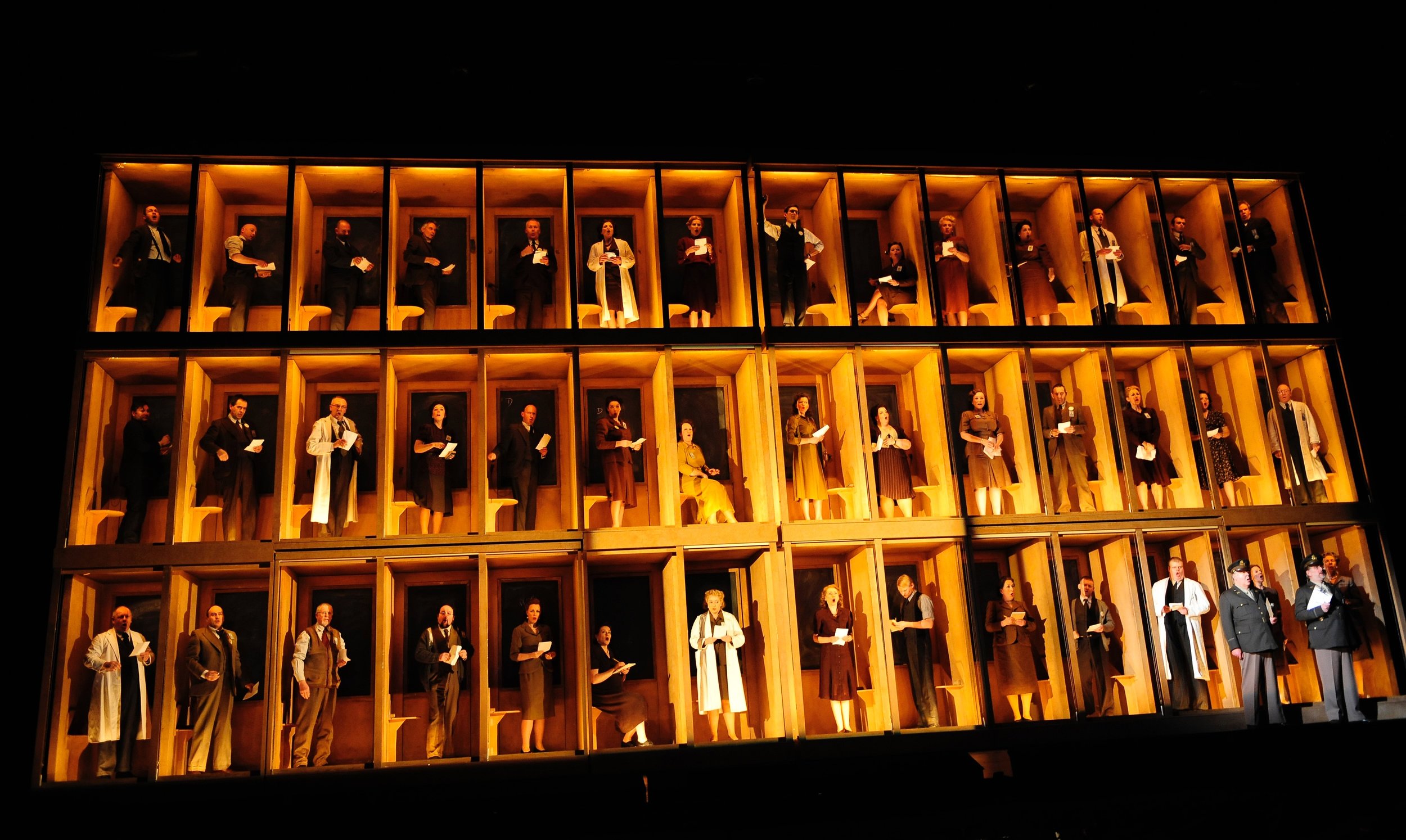

Then you move into the theatre and now you have the singers and the chorus on the set, the costumes, make-up, lighting and video projections to deal with. Doctor Atomic was very exciting because the audience didn’t know the piece and Brindley Sherrat who played Edward Teller said the audience felt like a hot bear pit of anticipation.

You can watch this production on the Metropolitan Opera website or buy the DVD.

https://www.amazon.com/Adams-Doctor-Atomic-Metropolitan-Opera/dp/B004EU7W5S

Here are some pictures and the programme notes I wrote for them.

DOCTOR ATOMIC – programme notes

Penny Woolcock

The day the world changed forever.

On September 12, 1933, a Hungarian Jewish refugee was standing on Southampton Row waiting for the traffic lights to change. He was Leo Szilard, a brilliant physicist and as the lights turned green he suddenly understood that the splitting of the atom could unleash a nuclear chain reaction to make a devastatingly destructive weapon.

In 1939 Szilard and his friend Enrico Fermi, conducted a simple experiment proving the viability of this chain reaction. Szilard was not in the mood to celebrate. “We turned the switch, saw the flashes, watched for ten minutes, then switched everything off and went home. That night I knew the world was headed for sorrow.”

Szilard knew that scientists who had remained in Nazi Germany had attended the same conferences and read all the same scientific papers and would be able to come to the same conclusion. Edward Teller, another Hungarian Jewish exile drove Szilard to see his friend Albert Einstein who arranged an interview with President Roosevelt and they persuaded him to fund an immense project to make the first atomic bombs in a race against the Nazis.

Robert Oppenheimer was chosen to run the research station at Los Alamos to make the plutonium bomb later dropped on Hiroshima. The New Mexico desert was sufficiently remote to keep the project secret and empty enough for the test. Oppenheimer was clever and charismatic and attracted the most talented scientists in the world – legends like Serber, Teller, Feynman, Bethe, Segre, and Bohr – to come and join him. Los Alamos was quickly populated with highly cultured, non-conformist geniuses. Oppenheimer himself was not only a fine physicist but a lover of art and poetry who had taught himself Sanscrit so he could read the Bhagavad Gita, (the great Hindu mystical text), in its original language. He was politically left wing and famous for throwing fundraising parties for radical causes. His first great love, Jean Tatlock, was a member of the Communist Party and his wife, Kitty a former member whose first husband had been killed fighting for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. Most of the European scientists were Jews who had fled the Nazis, and they fervently believed they were working against the clock to build the atomic bomb before Hitler got his hands on it.

General Groves, in charge of the military side of the project, considered these scientists ‘the greatest collection of crackpots the world has ever known’, an opinion he formed early on when Szilard insisted on taking a bath during their first encounter. He was never inclined to revise it. Most people hated him, but he was an effective leader. The army functions on unquestioning obedience and compartmentalization; scientists thrive on exchanging ideas and freedom of thought and it remained an uneasy marriage. Military men worried about the unreliable political affiliations of the ‘longhairs’, while scientists dismissed the soldiers as ‘plumbers’.

There was a third group at Los Alamos, the adult population of San Idelfonso, a Tewa Pueblo Indian village. An army truck scooped them up every morning and took them up the hill to carry out all the menial jobs – cleaning, childcare, stoking furnaces. They had very strong ideas of their own and a powerful alternative cosmology. While the ‘Anglo’ scientists were busy making a weapon to destroy the basic building blocks of the universe, the Tewa were dancing to keep everything in its place, still sorrowfully confident that we will eventually burn the earth to a crisp and only they will survive.

The race was on.

And then Germany surrendered. Japan was losing the war and already suing for peace. Neither country was anywhere near developing nuclear weapons. Lines between right and wrong were no longer clearly drawn.

This is where Doctor Atomic starts, two weeks before the first test. Leo Szilard, the man who had initiated the project – a man who knew so much about oppression that he lived in hotel rooms with a packed suitcase always on hand – sent a letter to his friend Edward Teller arguing that it was morally reprehensible to use the atomic bomb on Japan. Part of this extraordinary letter is sung in the opera. The young Quaker physicist Robert Wilson agreed and tried to get his fellow scientists to sign a petition suggesting they invite Japanese observers to the test and give them a chance to surrender before dropping the bomb.

But Oppenheimer was adamant. The test was scheduled to take place the night before the Potsdam conference at which Truman, Stalin, and Churchill were carving up the post-war world and Truman wanted a trump card up his sleeve to use against Stalin. Targets in Japan had already been chosen, densely populated, pristine targets that had not been fire-bombed, so they could see exactly how effective these new bombs would be.

The rest is history.

When the test bomb exploded successfully at Trinity, Oppenheimer stood up and stretched: ‘It worked.’ There was a celebration on the test site with plenty of drinking accompanied by Richard Feynman playing the bongos on the bonnet of a trunk. It was only after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima that many of the scientists became deeply depressed. Oppenheimer later said ‘I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ When he told Truman, ‘We physicists have known sin.’ Truman dismissed him as a ‘cry baby’.

Was it wrong to drop the bomb? The question of whether more lives would have been lost if Japan had fought on is a valid one. But isn’t that just a variant of ‘If I don’t do it, someone else will?’ There was a choice. Do the ends only justify the means when it is our side doing the choosing? Oppenheimer’s argument that it was better for him to remain a ‘voice within the government’ ends with him becoming a fig leaf for the ruthless annihilation of cities and then traduced and his security clearance revoked soon after he had served his purpose.

Doctor Atomic is about people who lived this dilemma: good, clever, kind, funny people. The average age at Los Alamos was twenty-five. These people worked hard, they partied hard, the birth rate sky-rocketed; they skied, rode horses, argued, and played the piano. Some of them deeply regretted the part they had played in ushering in the nuclear age; others did not. They were all seduced by the sheer audacity of the endeavour they were engaged in.

I am still deeply troubled by the way that people who condemn hundreds of thousands of civilians and their progeny to very painful deaths are exonerated, even praised, while an inner city youth who stabs another is considered almost sub human. I don’t understand it. There is nothing clever about this sentence, it is crude and disingenuous and I leave it here simply as a stone to catch in the throat before we swallow and move on.

There is a ravishing beauty in destruction. John Adams has composed a beautiful opera in Doctor Atomic and we have set out to create a production which captures both the beauty and the horror of its ambition.